Press Coverage

Click on the images to open the PDF document or full-size image

|

KPHTH Magazine - Monthly Publication of the Pancretan Association of America |

|||

|

August-September 2017 Special Report, page 25 |

December 2011 Front Cover |

March 2004 Front Cover Page 10 |

December 1999 Front Cover |

|

Trans-a-Gram - Monthly Publication of the Transfiguration Greek Orthodox Church |

|||

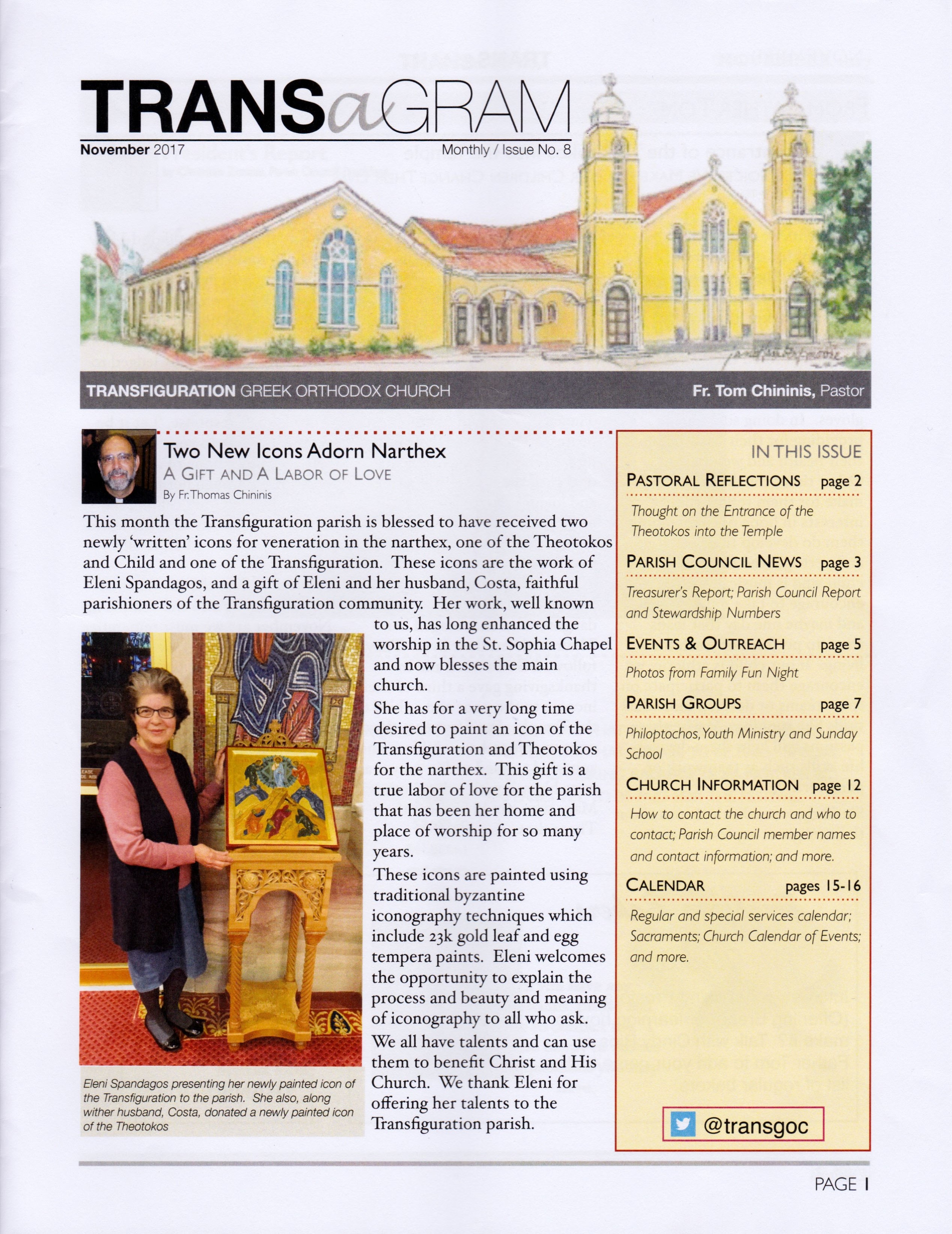

November 2017 Front Page |

April 2015 Page 3 |

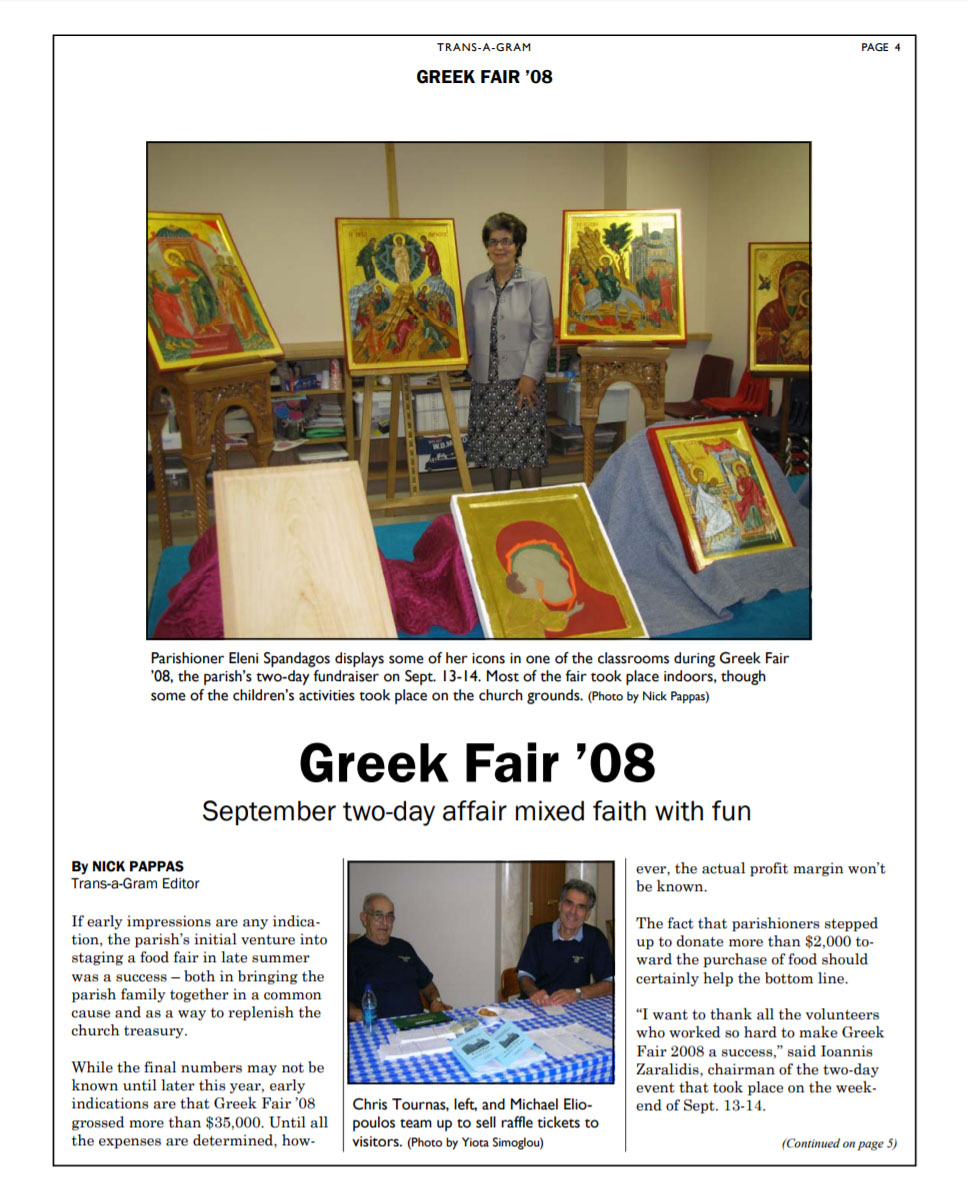

October 2008 Page 4 |

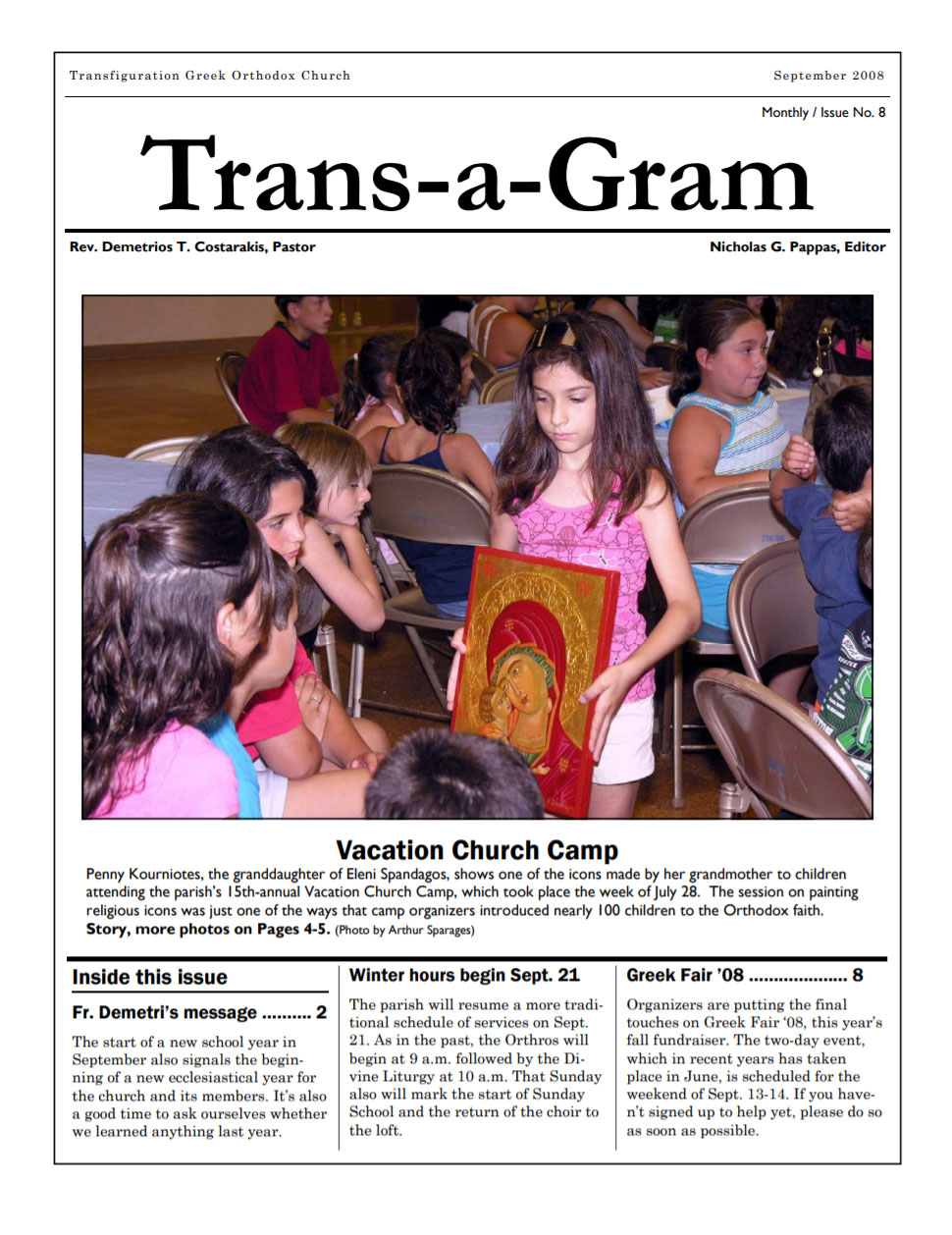

September 2008 Front Page |

|

|

|||

|

The Orthodox Observer

Monthly publication of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

December 2001 - Front Page

|

The Hellenic

Voice - Front Page, April 26, 2000

America's largest Greek-American newspaper (formerly The Hellenic Chronicle)

|

Reprinted from The Lowell Sun Newspaper, March 28, 1998:

An inspiring passion for Byzantine icons Tewksbury artist Eleni Spandagos expresses her spiritual life in the traditional images of her faith By CLAUDIA COMBS Byzantine icons have always inspired and fascinated local artist Eleni Spandagos of Tewksbury. From the age of five, Spandagos recalls, she was always attracted to the icons and frescoes that filled the Byzantine churches of the villages of Crete, Greece, where she grew up. "I would study the eyes, faces, and hands of the icons. It was as if I was drawn to them." Now, after a lifetime of artistic study and work--including 40 years as a wife, mother of a son and daughter, and occasional jobs outside the home as a seamstress and in high-tech--Spandagos has transformed her passion for iconography to become her main artistic focus. She is currently finishing an con of St. Thomas and will soon begin work on an icon of St. Andrew. They will complete a series of 12 icons that Spandagos has spent more than a year creating for St. Demetrios Church in Crete. Founded in the 4th century, St. Demetrios Church is located in the village where Spandagos' husband, Costas, spent his childhood. "A new church was built next door to the old St. Demetrios," Eleni Spandagos explains. "The new church did not have any icons and did not have much money. They supplied the wood for the icons. They are so happy to have these icons for their church." Spandagos' work is also generating some local attention. An exhibit featuring 21 of her icons will conclude this weekend at the Maliotis Cultural Center, 50 Goddard Ave. in Brookline where the artist's work has been on display since Oct. 13. For those who missed the opportunity to admire Spandagos' icons in person, and Internet Web page has been designed by her son, Vasilios (Bill). The site offers full and close-up views of 11 icons, as well as information about Eleni Spandagos. The address is http://www.gtba.net/iconography. Supporting Spandagos' iconography is a family project. Not only does son Bill promote the icons on the Internet, but daughter Olga photographs the artwork and produces brochures, cards announcements and advertising flyers. Husband Costas locates and prepares the wood on which Eleni paints the icons. She explains the long and intricate process involved with the wooden panels used for icons. "The best wood is a solid piece of pine walnut or cypress," she says, "the older the better." For the wood to be seasoned, Spandagos insists it must be at least 5 years old, but she notes that "some of my icons in the exhibit at the Maliotis Center are panted on 100-year old wood." Two channels are beveled from the back of the wooden panel, and strips of wood are hammered with a wooden mallet into each channel to strengthen the piece. A larger panel requires three back supports. The front of the wooden panel often has a raised border like a frame. A special glue mixture is spread on the front of the panel and a cheesecloth type of material is adhered to the surface. Next, a plaster solution made from charcoal, marble dust and rabbit skin glue is applied six times. Once smooth, the panel is ready for a finished pencil sketch to be transferred onto the surface of the wood. Every detail of the sketch--hands, face, eyes--must be exact. A thin layer of 23-karat (not 24-karat) Italian gold leafing is painstakingly applied to the background and finally, the color is painted on the panel using the egg tempera method--a solution of egg yolk, water and vinegar mixed with dry pigments and painted on the icon. "Once an icon is finished," Spandagos says, "varnish is applied which makes the painting strong. This is done because the pigments are very delicate." But the wood, glues, plaster and pigment solutions, and varnish are just the physical preparation involved in the art of iconography. Spandagos stresses that the spiritual and emotional aspects of creating icons are even more critical. "If you do not have the right feeling that you can reach only through prayer and reading the scripture, it is impossible to paint icons," she says. "If you are not at peace, you cannot work. You can sit there for hours in front of your work and nothing comes out, nothing happens." Spandagos also notes that centuries of tradition have created similarities between the works of Byzantine iconographers. She specifically mentions the elongated faces, large almond shaped eyes, striped patters on clothing, colors, and Greek letters used in every icon. But she also quickly points out that there are also enormous differences among icons. "These art works represent your own feelings, your own emotions," Spandagos says. "The faces in icons always look at you and have communication with people. The faces always look peaceful. Every iconographer has a different expression. It might be the same Byzantine art, but everyone has their own artistic expression." The pursuit of artistic excellence and knowledge is nonstop for Spandagos. She reads constantly about iconography, travels extensively, and frequently attends exhibits featuring ancient and current works of iconographers. Last summer she toured Turkey and visited many old churches--most in ruins, destroyed during years of political turmoil. She studied the colors and details of what remained on the scratched and damaged walls and says she felt the depth of joy and the spirituality in the art work. She also cried as she observed the scraped eyes and faces of these holy masterpieces. Despite the heart-wrenching destruction she witnessed, Spandagos says she returned to the United States bubbling with artistic fervor and filled with ideas for her own work. "The old icons are the best teachers," she says with a grin. "I study and learn all the time. There is always something new. There are so many details and I will continue to learn until my last day. One thing that makes me very happy is to work and learn about iconography. |